What is Structural Design Pattern?

Structural design patterns explain how to assemble objects and classes into larger structures while keeping these structures flexible and efficient.

In the last blog, we explore creational design patterns in Kotlin, if you haven’t read it check the below link 👇

Design patterns with Kotlin Part 1

Let’s start exploring structural patterns,

1. Adapter Pattern

Adapter design pattern allows objects with incompatible interfaces to collaborate.

Problem:

Imagine that you’re creating a stock market monitoring app. The app downloads the stock data from multiple sources in XML format and then displays nice-looking charts and diagrams for the user.

At some point, you decide to improve the app by integrating a smart 3rd-party analytics library. But there’s a catch: the analytics library only works with data in JSON format

Solution:

You can create an adapter. This is a special object that converts the interface of one object so that another object can understand it.

An adapter wraps one of the objects to hide the complexity of conversion happening behind the scenes. The wrapped object isn’t even aware of the adapter. For example, you can wrap an object that operates in meters and kilometres with an adapter that converts all of the data to imperial units such as feet and miles.

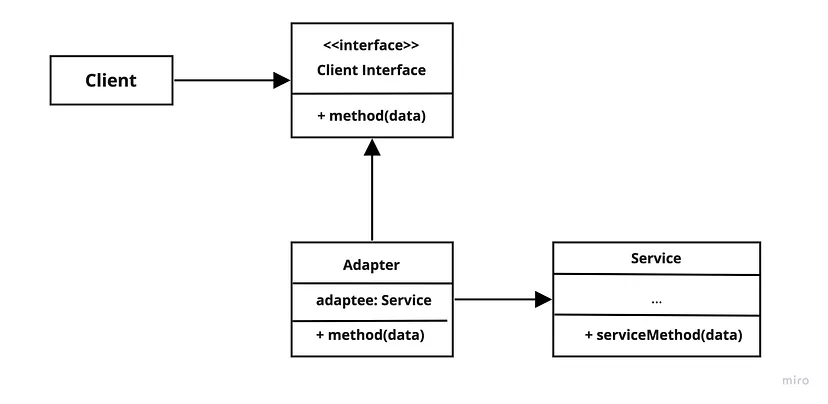

Adapter Pattern 1.0

Adapter Pattern 1.0

This implementation uses the object composition principle: the adapter implements the interface of one object and wraps the other.

Let’s jump on code implementation,

| // 3rd party functionality | |

| data class DisplayDataType(val index: Long, val data: String) | |

| class DataDisplay { | |

| fun display(display: DisplayDataType) { | |

| println("Data:- ${display.index}-${display.data}") | |

| } | |

| } | |

| // Our code | |

| data class DatabaseData(val position: Long, val amount: Double) | |

| class DatabaseDataGenerator { | |

| fun generate(): List<DatabaseData> { | |

| val list = arrayListOf<DatabaseData>() | |

| list.add(DatabaseData(position = 1, amount = 200.0)) | |

| list.add(DatabaseData(position = 2, amount = 400.0)) | |

| return list | |

| } | |

| } | |

| interface DatabaseDataConverter { | |

| fun convertData(data: List<DatabaseData>): List<DisplayDataType> | |

| } | |

| class DisplayDataAdaptor(val dataDisplay: DataDisplay) : DatabaseDataConverter { | |

| override fun convertData(data: List<DatabaseData>): List<DisplayDataType> { | |

| val result = arrayListOf<DisplayDataType>() | |

| data.forEach { | |

| val ddt = DisplayDataType(index = it.position, data = it.amount.toString()) | |

| dataDisplay.display(ddt) | |

| result.add(ddt) | |

| } | |

| return result | |

| } | |

| } | |

| fun main() { | |

| val generator = DatabaseDataGenerator() | |

| val generatedData = generator.generate() | |

| val adaptor = DisplayDataAdaptor(DataDisplay()) | |

| adaptor.convertData(generatedData) | |

| } | |

| /* output | |

| Data:- 1-200.0 | |

| Data:- 2-400.0 | |

| */ |

Pros:

- Single Responsibility Principle. You can separate the interface or data conversion code from the primary business logic of the program.

- Open/Closed Principle. You can introduce new types of adapters into the program without breaking the existing client code, as long as they work with the adapters through the client interface

Cons:

- The overall complexity of the code increases because you need to introduce a set of new interfaces and classes. Sometimes it’s simpler just to change the service class so that it matches the rest of your code.

2. Decorator Pattern

Decorator design pattern that lets you attach new behaviours to objects by placing these objects inside special wrapper objects that contain the behaviours.

The Decorator pattern allows us to add behaviour either statically or dynamically by providing an enhanced interface to the original object. The static approach can be achieved using inheritance, overriding all the methods of the main class and adding the extra functionality that we want.

As an alternative to inheritance and to reduce the overhead of subclassing, we can use composition and delegation to add additional behaviour dynamically. In this article, we’ll follow these techniques for the implementation of this pattern.

Problem:

Suppose you’re working on a simple API where you have to read/write data for this you’ll create simple functions but what if tomorrow you want to do extra operations li*ke encryption? you need to so many changes in functions and this will also break the Single-responsibility principle

Solution:

The solution to the above problem is overriding all the methods of the main class and adding extra functionality i.e encryption/decryption to that respective action

Let’s jump into the code to understand it,

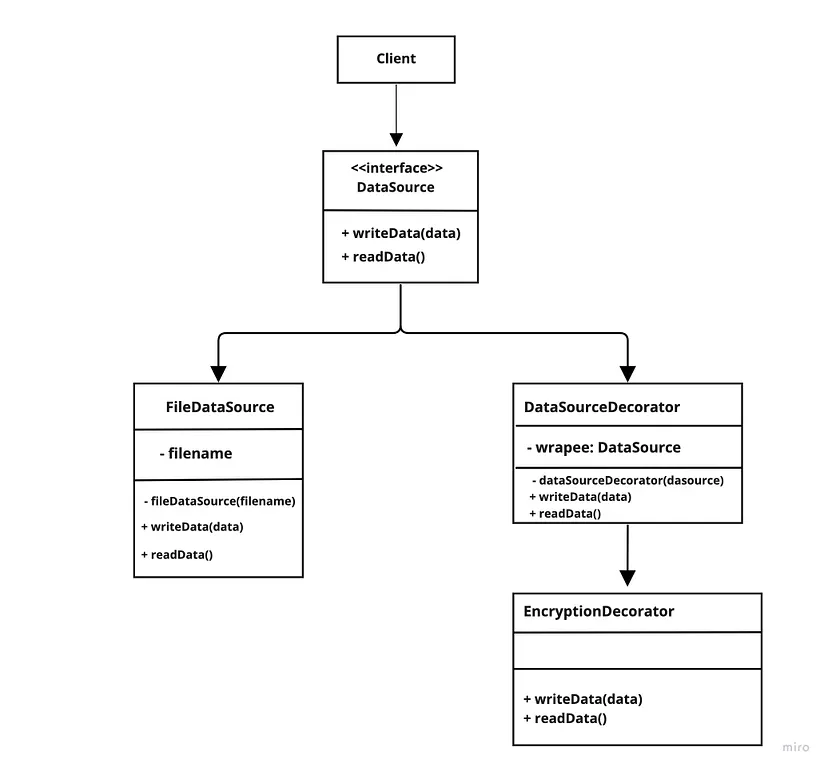

Decorator Pattern 1.0

Decorator Pattern 1.0

| import java.io.IOException | |

| import java.io.FileReader | |

| import java.io.FileOutputStream | |

| import java.io.OutputStream | |

| interface DataSource { | |

| fun writeData(data: String) | |

| fun readData(): String | |

| } | |

| class FileDataSource(private val name: String) : DataSource { | |

| override fun writeData(data: String) { | |

| val file = File(name) | |

| try { | |

| FileOutputStream(file).use { fos -> fos.write(data.toByteArray(), 0, data.length) } | |

| } catch (ex: IOException) { | |

| println(ex.message) | |

| } | |

| } | |

| override fun readData(): String { | |

| var buffer: CharArray? = null | |

| val file = File(name) | |

| try { | |

| FileReader(file).use { reader -> | |

| buffer = CharArray(file.length() as Int) | |

| reader.read(buffer) | |

| } | |

| } catch (ex: IOException) { | |

| println(ex.message) | |

| } | |

| return String(buffer) | |

| } | |

| } | |

| class DataSourceDecorator internal constructor(private val wrappee: DataSource) : DataSource { | |

| fun writeData(data: String?) { | |

| wrappee.writeData(data!!) | |

| } | |

| override fun readData(): String { | |

| return wrappee.readData() | |

| } | |

| } | |

| class EncryptionDecorator(source: DataSource?) : DataSourceDecorator(source!!) { | |

| override fun writeData(data: String) { | |

| super.writeData(encode(data)) | |

| } | |

| override fun readData(): String { | |

| return decode(super.readData()) | |

| } | |

| private fun encode(data: String): String { | |

| val result: ByteArray = data.toByteArray() | |

| for (i in result.indices) { | |

| (result[i] += 1.toByte()).toByte() | |

| } | |

| return Base64.getEncoder().encodeToString(result) | |

| } | |

| private fun decode(data: String): String { | |

| val result: ByteArray = Base64.getDecoder().decode(data) | |

| for (i in result.indices) { | |

| (result[i] -= 1.toByte()).toByte() | |

| } | |

| return String(result) | |

| } | |

| } |

See the above example we simply added EncryptionDecorator and all the necessary logic related to Encryption is in this class itself.

Pros:

- You can extend an object’s behaviour without making a new subclass.

- You can add or remove responsibilities from an object at runtime.

- Single Responsibility Principle. You can divide a monolithic class that implements many possible variants of behaviour into several smaller classes.

Cons:

- It’s hard to implement a decorator in such a way that its behaviour doesn’t depend on the order in the decorators stack.

3. Facade

Facade pattern provides a simplified interface to a library, a framework, or any other complex set of classes.

Problem:

Imagine that you must make your code work with a broad set of objects that belong to a sophisticated library or framework. Ordinarily, you’d need to initialize all of those objects, keep track of dependencies, execute methods in the correct order, and so on.

As a result, the business logic of your classes would become tightly coupled to the implementation details of 3rd-party classes, making it hard to comprehend and maintain.

Solution:

A facade is a class that provides a simple interface to a complex subsystem which contains lots of moving parts. A facade might provide limited functionality in comparison to working with the subsystem directly. However, it includes only those features that clients really care about.

Having a facade is handy when you need to integrate your app with a sophisticated library that has dozens of features, but you just need a tiny bit of its functionality.

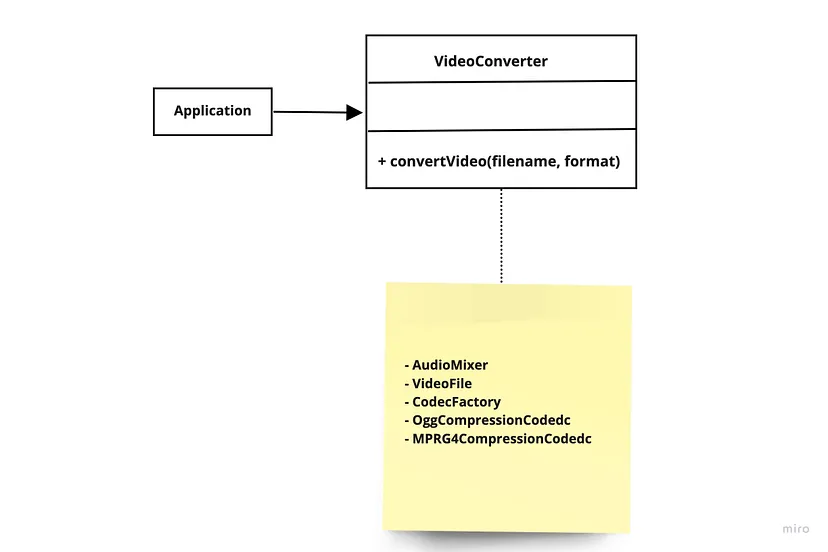

Facade 1.0

Facade 1.0

Instead of making your code work with dozens of the framework classes directly, you create a facade class which encapsulates that functionality and hides it from the rest of the code. This structure also helps you to minimize the effort of upgrading to future versions of the framework or replacing it with another one. The only thing you’d need to change in your app would be the implementation of the facade’s methods.

| import BitrateReader.convert | |

| import BitrateReader.read | |

| import CodecFactory.extract | |

| import java.io.File; | |

| class VideoFile(private val name: String) { | |

| val codecType: String = name.substring(name.indexOf(".") + 1) | |

| } | |

| interface Codec { | |

| } | |

| class MPEG4CompressionCodec : Codec { | |

| var type = "mp4" | |

| } | |

| class OggCompressionCodec : Codec { | |

| var type = "ogg" | |

| } | |

| object CodecFactory { | |

| fun extract(file: VideoFile): Codec { | |

| val type = file.codecType | |

| return if (type == "mp4") { | |

| println("CodecFactory: extracting mpeg audio...") | |

| MPEG4CompressionCodec() | |

| } else { | |

| println("CodecFactory: extracting ogg audio...") | |

| OggCompressionCodec() | |

| } | |

| } | |

| } | |

| object BitrateReader { | |

| fun read(file: VideoFile, codec: Codec?): VideoFile { | |

| println("BitrateReader: reading file...") | |

| return file | |

| } | |

| fun convert(buffer: VideoFile, codec: Codec?): VideoFile { | |

| println("BitrateReader: writing file...") | |

| return buffer | |

| } | |

| } | |

| class AudioMixer { | |

| fun fix(result: VideoFile?): File { | |

| println("AudioMixer: fixing audio...") | |

| return File("tmp") | |

| } | |

| } | |

| class VideoConversionFacade { | |

| fun convertVideo(fileName: String?, format: String): File { | |

| println("VideoConversionFacade: conversion started.") | |

| val file = VideoFile(fileName!!) | |

| val sourceCodec = extract(file) | |

| val destinationCodec: Codec = if (format == "mp4") { | |

| MPEG4CompressionCodec() | |

| } else { | |

| OggCompressionCodec() | |

| } | |

| val buffer = read(file, sourceCodec) | |

| val intermediateResult = convert(buffer, destinationCodec) | |

| val result = AudioMixer().fix(intermediateResult) | |

| println("VideoConversionFacade: conversion completed.") | |

| return result | |

| } | |

| } | |

| fun main(args: Array<String>) { | |

| val converter = VideoConversionFacade() | |

| val mp4Video = converter.convertVideo("youtubevideo.ogg", "mp4") | |

| // ... | |

| } |

Pros:

- You can isolate your code from the complexity of a subsystem.

Cons:

- Tightly coupled classes

4. Proxy Pattern

Proxy design pattern that lets you provide a substitute or placeholder for another object. A proxy controls access to the original object, allowing you to perform something either before or after the request gets through to the original object.

Problem:

Suppose you have a massive object that consumes a vast amount of system resources. You need it from time to time, but not always. In an ideal world, we’d want to put this code directly into our object’s class, but that isn’t always possible. For instance, the class may be part of a closed 3rd-party library.

**Solution:

The Proxy pattern suggests that you create a new proxy class with the same interface as an original service object. Then you update your app so that it passes the proxy object to all of the original object’s clients. Upon receiving a request from a client, the proxy creates a real service object and delegates all the work to it.

In the Proxy Pattern, a client does not directly talk to the original object, it delegates its calls to the proxy object which calls the methods of the original object.

| interface File { | |

| fun read() | |

| } | |

| class NormalFile(val name: String) : File { | |

| override fun read() = println("Reading file: $name") | |

| } | |

| //Proxy: | |

| class SecuredFile(val name: String) : File { | |

| val normalFile = NormalFile(name) | |

| var password: String = "" | |

| override fun read() { | |

| if (password == "secret") { | |

| println("Password is correct: $password") | |

| normalFile.read() | |

| } else { | |

| println("Incorrect password. Access denied!") | |

| } | |

| } | |

| } | |

| fun main(args: Array<String>) { | |

| val securedFile = SecuredFile("readme.md") | |

| securedFile.read() | |

| securedFile.password = "secret" | |

| securedFile.read() | |

| } |

Pros:

- You can control the service object without clients knowing about it.

- Open/Closed Principle. You can introduce new proxies without changing the service or clients.

Cons:

- The code may become more complicated since you need to introduce a lot of new classes.

5. Bridge Pattern

The bridge pattern allows the Abstraction and the Implementation to be developed independently and the client code can access only the Abstraction part without being concerned about the Implementation part.

Problem:

When there are inheritance hierarchies creating concrete implementation, you lose flexibility because of interdependence.

Solution:

Decouple implementation from the interface and hiding implementation details from the client is the essence of the bridge design pattern

Check the below code snippet 👇

| package structural | |

| interface Switch { | |

| var appliance: Appliance | |

| fun turnOn() | |

| } | |

| interface Appliance { | |

| fun run() | |

| } | |

| class RemoteControl(override var appliance: Appliance) : Switch { | |

| override fun turnOn() = appliance.run() | |

| } | |

| class TV : Appliance { | |

| override fun run() = println("TV turned on") | |

| } | |

| class VacuumCleaner : Appliance { | |

| override fun run() = println("VacuumCleaner turned on") | |

| } | |

| fun main(args: Array<String>) { | |

| var tvRemoteControl = RemoteControl(appliance = TV()) | |

| tvRemoteControl.turnOn() | |

| var fancyVacuumCleanerRemoteControl = RemoteControl(appliance = VacuumCleaner()) | |

| fancyVacuumCleanerRemoteControl.turnOn() | |

| } |

Pros:

- Bridge pattern allows independent variation between two abstract and implementor systems.

- It avoids the client code binding to a certain implementation.

- Abstraction and implementation can be clearly separated allowing the easy future extension.

Cons:

- You might make the code more complicated by applying the pattern to a highly cohesive class.

In this blog, we covered structural design patterns with their example in Kotlin. For more examples check out our Github Repository here. In the upcoming blogs, we’ll be exploring Behavioural Patterns.

At Scalereal We believe in Sharing and Open Source.

So, If you found this helpful please give some claps 👏 and share it with everyone.

Sharing is Caring!

Thank you ;)